I am writing Dora, a simple JIT-compiler with Rust. Dora is both the name of the custom programming language and of the JIT-compiler. After some time working on it, I want to write about the experiences I made. I started this project to get a better understanding of the low-level implementation details of a JIT-Compiler.

Architecture Link to heading

The architecture is pretty simple: dora hello.dora parses the given input file into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). After parsing, the whole AST is semantically checked, if this succeeds execution starts with the main function.

To execute main, machine-code is generated for that function by the baseline compiler by traversing the AST nodes of the function.

The function is traversed twice, first to generate information (mostly about the stack frame), the second traversal then generates the machine code.

The baseline compiler is a method-based compiler and not a tracing JIT like for example LuaJIT. The purpose of the baseline compiler in Dora is to generate code as fast as possible, not to generate the most efficient code. The sooner it finishes code generation, the sooner execution can start.

Many VMs like the OpenJDK or V8 pair the baseline compiler (and/or interpreter) with one or more optimizing compilers that compile functions to more efficient machine-code if it detects a function to be hot. The optimizing compiler needs longer to compile a given function, but generates more optimized machine-code. This is acceptable since not all code gets compiled by the optimizing compiler but only hot code/functions. Dora doesn’t have an optimizing compiler at the moment, but I have plans to implement one.

Compilation Link to heading

The baseline compiler uses a MacroAssembler to generate machine code. All differences between different Instruction Set Architectures (ISAs) are handled by the MacroAssembler. Dora can generate machine-code for x86_64 and AArch64. Adding other ISAs should be possible without touching the baseline compiler.

Implementing the second ISA certainly helped making the architecture cleaner and even unveiled bugs I didn’t notice on x86_64.

It was also pretty interesting to implement instruction encoding, both for x86_64 and AArch64.

I didn’t implement instruction decoding myself, for this purpose I used the capstone library.

The generated machine-code can be emitted with dora --emit-asm=all hello-world.dora.

A nice feature of the MacroAssembler is that comments can be added to the generated instructions.

When disassembling the comments are printed along the disassembled machine instructions:

fn main() 0x7f33bab6d010

0x7f33bab6d010: pushq %rbp

0x7f33bab6d011: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x7f33bab6d014: subq $0x10, %rsp

; prolog end

; load string

0x7f33bab6d018: movq -0x17(%rip), %rax

0x7f33bab6d01f: movq %rax, -8(%rbp)

0x7f33bab6d023: movq -8(%rbp), %rdi

; call direct println(Str)

0x7f33bab6d027: movq -0x2e(%rip), %rax

0x7f33bab6d02e: callq *%rax

; epilog

0x7f33bab6d030: addq $0x10, %rsp

0x7f33bab6d034: popq %rbp

0x7f33bab6d035: retq

There already exists a Rust wrapper for the capstone libary. Although the README states that the bindings are incomplete, the wrapper supported all the features I need.

The Dora programming language Link to heading

Here is a simple Hello world program:

fun main() {

println("Hello World");

}

Dora is a custom-language with similarities to languages like Java, Kotlin and Rust (for Rust it is only syntactical). Most importantly: Dora is statically-typed and garbage collected. Dora is still missing a lot, I planned to add more but writing a JIT is more than enough work. Instead of adding more syntactic sugar, I preferred to implement features that were more interesting to implement in the JIT.

Nevertheless Dora alredy has quite a large number of features.

This are the supported primitive types: bool, byte, char, int, long, float, double.

It is also possible to define your own classes (with inheritance) just like Java/Kotlin/etc.

class Point(let x: int, let y: int)

// generic classes are supported too

class Wrapper<T>(let obj: T)

Dora also supports variable-sized objects like Arrays with the Array<T> class and Strings with Str.

These object types need to be treated differently both when allocating and collecting compared to fixed-size objects/classes like Point in the example above (their size depends on the length-field).

What’s also important to note for generic classes: Unlike Java, generic types can also be primitive types.

So Wrapper<int> and Wrapper<bool> are both valid and are internally represented as two different classes.

Since a few a weeks Dora also supports generic trait boundaries, such that designing a fast generic hashing key-value mapping implementation should be possible.

I didn’t yet write a generic HashMap but you can look into the implementation of SlowMap in the testsuite which should show that this should be feasibles.

But why didn’t I use an already existing language? The main reason: I didn’t intend to implement that many features into the language. All I wanted was a simple, staticaly typed language which I could easily generate machine code for.

Instead of using an already existing language, I could’ve also used an intermediate representation or bytecode like WASM or Java Bytecode. This would’ve meant that I could get a lot of benchmarks for my JIT and I could easily compare results to other VMs. To be honest, today this sounds a lot more feasible than it was back then. There are so many features you need to implement to run any non-trivial benchmark, I didn’t think it was feasible to run any non-trivial program. A big obstacle in writing complex benchmarks for Dora is the missing standard library: This could’ve been solved by using e.g. Classpath or OpenJDK. So this might have been easier, but still it was certainly also interesting to “design” a programming language. If I think about it, WASM is probably not ideal right now since I also wanted to look into garbage collection.

Another feature Dora supports are Exceptions.

Exceptions can be thrown with throw, while do, catch and finally are used to catch exceptions.

Doras exception handling is similar to Swift, all functions that can throw exceptions need to be marked with throws:

fun foo() throws { /* ... */ }

Functions that can throw need to be invoked like try foo() or try obj.bar(), where try is just syntactic sugar that signals a potentially throwing invocation.

I like this syntax because it makes it obvious in the caller that an exception could occur.

For runtime errors like failed assertions, the program is halted and the current stack trace is printed. Although exceptions and stack traces sound quite unspectacular, I was quite happy when this worked for the first time.

Dora also supports inheritance for classes.

It has primary and secondary constructors like Kotlin.

The keyword is is similar to Javas instanceof, while as is used for the checked cast (in Java you would write (SomeClass) obj for that).

I implemented this check as described in this great paper from Cliff Click and John Rose.

Unfortunately I haven’t benchmarked my implementation of the fast subtype check yet.

My implementation is a bit easier since Dora doesn’t have interfaces or dynamically loaded classes.

Garbage Collection Link to heading

Dora has an exact, tracing Garbage Collector. For a tracing GC to work, it is essential to determine the root set. The root set is the initial set of objects for object graph traversal. The set usually consists of global variables and/or local variables.

While it is quite easy to add global variables to the root set, this is much harder for local variables. For this we need working stack unwinding, Dora needs to examine the active functions on the stack. Although we then know all local variables in these functions, there is one more complication:

fun foo() {

let x = A(); // create object of class A

bar1(); // GC Point 1

let y = A(); // create another object of class A

bar2(); // GC Point 2

// use x and y

}

For determining local variables we also need to know where in a function we currently are.

The Dora function foo has two local variables, but when invoking bar1 only x is initialized.

At this point there is already space reservered for y but the memory is still uninitialized and contains some random value.

y shouldn’t be part of the root set at that point.

When invoking bar2 both x and y are initialized and therefore both belong to the root set.

The baseline compiler keeps track of initialized local variables and emits so called GC points for each function invocation. The GC point stores which local variables are initialized. Now there is enough information to collect all local variables from the stack. To be more precise Dora not only keeps track of local variables but also of temporary values, fortunately temporary values can just be treated like local variables.

My first implementation of the GC was a Mark-and-Sweep collector which simply used malloc for object allocation and free for object deallocation.

The marking phase marked every object that was reachable. The sweeping phase afterwards invoked free for every object that wasn’t marked.

The problem with this implementation was to keep track of all allocated objects: the whole heap was a single linked-list.

Each object had an additional word to store the pointer to the next object.

This increased object sizes but also made traversing the heap quite cache-inefficient.

malloc & free are also quite expensive.

I don’t want to say they are slow, they are not.

But within a managed heap we can do better.

That’s why I wrote a simple Copy Collector using the Cheney-Algorithm. A copy collector divides a heap into two equally-sized spaces: the from and to space. Objects are always allocated in the from space, by increasing a pointer that points to the next free memory by the object size. As soon as this pointer reaches the end of the space, all surviving objects are copied from the from space to the to space. All live objects are now in the to space, the from space now only contains garbage. The spaces then switch roles. Deallocation of unreachable/dead objects is a no-op.

I liked that I could implement this collector in less than 200 lines of code and it is also quite performant for the amount of work that went into it. The GC Handbook recommends this algorithm if your goal is just to have a simple and working GC with good performance. The obvious disadvantage of this collector type is that 50% of the heap are always unusable. Copying live objects can be quite expensive too if a lot of objects survive, that also means potentially long pause times. These disadvantages also explain why a copy collector is quite common in the young generation of many garbage collectors. For one the young generation is only a (small?) part of the heap, so not that much memory is unusable. Furthermore if a program fulfills the generational hypothesis (that means most objects die young), copying should also be quite cheap.

For me there was another property of copy collectors that was really important: moving objects. Since the address of an object can change, global variables and local variables in the root set need to be updated to point to the new address of the object while collecting garbage. My initial Mark-and-Sweep-GC didn’t move any object. This gave me more confidence that my root set was actually correct and updating references was working.

I added a flag --gc-stress which forces a collection at every single allocation.

This is horribly inefficient but was invaluable for testing my implementation.

You might also force a garbage collection by invoking forceCollect() from Dora.

Another interesting problem for the GC are references into the heap from native code. Imagine a native function like this:

fn some_native_function() {

let obj1: *const Obj = gc.allocate_object();

let obj2: *const Obj = gc.allocate_object();

// do something with obj1 and obj2

}

The second object allocation might cause a garbage collection.

If this is the case the first object is not part of the root set since only a local variable in native code references this object.

Dora doesn’t have any knowledge about stack frames and local variables of native Rust code and will never have.

The object wouldn’t survive the collection, but even if it would, obj would point to the wrong address (the copy collector moves all surviving objects).

Somehow we need to add this object to the root set.

To solve this I added a data structure HandleMemory and a type Rooted<T> that stores an indirect pointer to an object.

The native function from above now looks like this:

fn some_native_function() {

let obj1: Rooted<Obj> = root(gc.allocate_object());

let obj2: Rooted<Obj> = root(gc.allocate_object());

// do something with obj1 and obj2

}

HandleMemory is used to store direct pointers into the heap, all entries are automatically part of the root set.

Rooted<Obj> is a pointer to an entry in the handle memory and therefore an indirect pointer.

The function root stores the direct pointer it gets from the object allocation in HandleMemory and returns an indirect pointer for this entry.

This solves heap references from local variables in native code into the heap.

HandleMemory is cleaned up when the native code returns to Dora code.

This makes it invalid to retain these indirect pointers by storing it in some global variable.

If I should have a need for this later, I would need to add some kind of global references.

Actually the whole integration between the GC or JIT and native code is quite interesting. Right now I am working again to improve the GC. My first goal here is to write a generational GC called Swiper. This should make GC pauses way shorter than with the current Copy GC. I also have other improvements in mind: incremental marking, Thread-Local Allocation Buffer, etc.

Benchmarks Link to heading

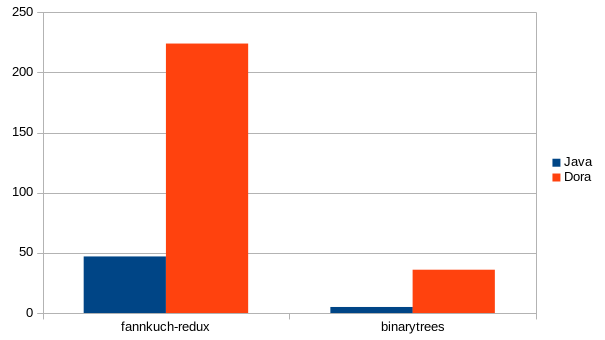

I can’t finish writing this blog without showing some benchmark results. There are at least two microbenchmarks Dora is able to run right now from the Language Benchmarks Game: fannkuch-redux and binarytrees. I chose the fastest single-threaded Java implementation (dora does not support multi-threading yet) of these benchmarks and translated them to Dora.

For fannkuch-redux Dora is about 4.7 times (47s to 224s) slower than the Java equivalent running on OpenJDK (version 1.8.0_144), the benchmark results for binarytrees are worse: Dora is 7.2x slower (36s instead of 5s).

This is easily explained: binarytrees stresses the GC and the current implementation isn’t really the most efficient.

We will later look into this benchmark in more detail.

Nevertheless I am satisfied with these numbers. Neither did I cheat nor am I expecting these numbers to get significantly worse when adding more features.

It should be clear but just to make sure: Please don’t draw any conclusions on Rusts performance from these benchmarks. All time is spent in the generated machine-code, the code generator for Dora is at fault not Rust.

Dora with perf Link to heading

We can look deeper into the binarytrees benchmark and run the program with perf.

perf can record stacktraces using sampling.

Thanks to Brendan Gregg we can create flame graphs as interactive SVGs from the collected stacktraces, which is pretty cool:

What’s also pretty nice is that perf shows both user and kernel stack traces.

perf even emits the function names for the jitted functions, which was actually pretty easy to achieve.

All you need to do is to create a file /tmp/perf-<pid>.map that consists of lines with this format:

<code address start> <length> <function name>

Dora just needs to emit such lines for every jitted function.

What can we conclude from this performance analysis? According to the measurements, mutex locking & unlocking takes a large part of the runtime (~25%). Right now, allocation happens in a mutex (even though Dora is still single-threaded). I plan to get rid of this with my new generational collector, this should give a nice speedup. But for now I will leave it as it is.

What also shows up in the profile are the functions start_native_call and finish_native_call (8-9% of the runtime).

Calling a native function is more expensive than calling a normal Dora function.

start_native_call and finish_native_call do the necessary setup- and cleanup-work for calling a native function.

Object allocation is the only native function regularly invoked in this benchmark.

By inlining the object allocation, we can get rid of the native function calling overhead.

I need working Thread-Local Allocation Buffers (TLABs) in my GC for that, Swiper should enable that optimization.

Optimizing Compiler Link to heading

Another feature I want to implement is an optimizing compiler for Dora. This would probably improve almost every benchmark. I think that Dora is already expressive enough to write the optimizing compiler in Dora instead of Rust. This could also be a great test case for Dora. The baseline compiler emits machine code from the AST, which are quite a lot of different Rust data structures. I suppose it would be quite cumbersome to pass the Rust AST to Dora. Therefore I would first emit byte code in Rust, and then simply pass the byte code array to Dora. This should be way easier. I would then have a “sea of nodes” IR in Dora on which I could do all my optimizations. That said this is probably going to take some time. Nevertheless I am already looking forward to implement it.

Using Rust Link to heading

A few words on using Rust: I started the project to try out Rust on a non-trivial project.

I knew some Rust but hadn’t used it on a project before.

Both cargo and rustup are great tools.

They also work on my Odroid C2 where I implemented the support for AArch64.

Cross-compiling became pretty easy, although I just used it for making sure Dora still builds on AArch64

(I never bothered to try to get it to link).

Cross-building is as simple as cargo build --target=aarch64-unknown-linux-gnu.

What was especially hard for me to get used to was exclusive mutability, not really borrowing or ownership. I am perfectly aware that this feature is the reason I don’t have to worry about iterator invalidation or data races in safe rust code but still it takes some time getting used to. The good thing about that though, it forces you to think about organizing your data structures more thoroughly.

Conclusion Link to heading

Implementing both a programming language and JIT is a LOT of work. Nevertheless working on it was and still is both fun and educational and there will always be so much stuff that would be cool to implement or to improve. The source is on Github, contributions are welcome.