JavaScriptCore (JSC, WebKit’s JavaScript engine) needs to be able to parse/unwind the call stack for exception handling or determining stack traces. This is not so simple since JS and native/C++ can be arbitrarily intertwined and JS call frames do not match the system’s calling convention. On the other hand while JSC controls JS stack frames and knows how to unwind them, it can’t do the same thing for native C++ stack frames since this is defined by the compiler (its flags) and/or system. This document describes how JSC still manages to unwind the stack.

JSC’s Calling Convention Link to heading

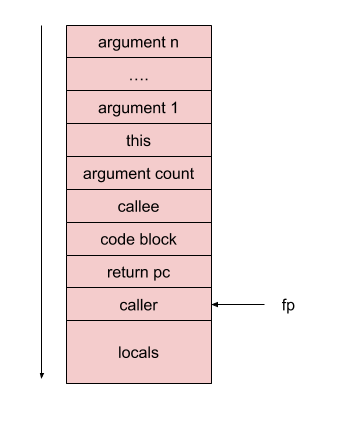

JSC uses its own calling-convention for JS-Functions. This convention is used by the interpreter, the baseline JIT and its optimizing compilers DFG and FTL, such that JS-functions emitted by different compilers are able to interoperate with each other.

All arguments are passed on the stack, there are also some additional values passed as argument.

Calling JS-Functions from C++ Link to heading

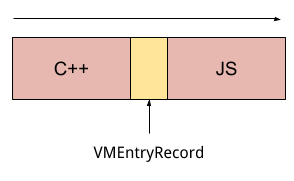

JSC’s calling convention is quite different to the one used by C++. That means that C++ can’t directly call JS-Functions compiled by JSC - there needs to be an intermediate step.

In JSC this intermediate step is vmEntryToJavaScript that is called by C++. It has quite some responsibilities:

- allocates and initializes a VMEntryRecord on the stack, that is later used for stack unwinding,

- it pushes the arguments on the stack but also everything else that is required by JSC’s calling convention,

- executes the actual JS-Function,

- and after function execution it removes the stack frame and returns to the caller.

Not all JS-Functions in JSC are implemented in JS, some are actually implemented in C++. Although written in C++, they still make use of JSC’s calling convention for passing arguments. Here is an example for a JS-function implemented in C++:

EncodedJSValue JSC_HOST_CALL functionSleepSeconds(ExecState* exec)

{

VM& vm = exec->vm();

auto scope = DECLARE_THROW_SCOPE(vm);

if (exec->argumentCount() >= 1) {

Seconds seconds = Seconds(exec->argument(0).toNumber(exec));

RETURN_IF_EXCEPTION(scope, encodedJSValue());

sleep(seconds);

}

return JSValue::encode(jsUndefined());

}

All these functions have exactly one argument: an ExecState-pointer.

The frame pointer in JSC’s calling convention is passed to this argument.

Arguments and callers can be accessed via this pointer (e.g. exec->argument(0) to get the first argument).

That means there are two ways to enter the VM from C++: via a real JS function or a JS function that is backed by native code.

The first way is handled by vmEntryToJavaScript, the other one by vmEntryToNative.

Again, note that vmEntryToNative is used when JS functions implemented in C++ are called from C++.

Calling C++ from JS Link to heading

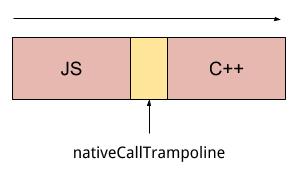

JS functions can also call back into the runtime (native functions) for certain operations: there needs to be an additional intermediate step again.

nativeCallTrampoline does this translation, it passes the call frame (the ExecState-pointer) as a single argument to the C++-function.

It also stores the current call frame in VM::topCallFrame, but we will later cover that in more detail.

nativeCallTrampoline also obviously calls the native function.

When it returns it checks VM::m_exception whether the C++-function has thrown an exception and would call into exception handling if so.

It then returns to the caller JS function.

Stack Unwinding Link to heading

JS and C++-stack frames can be arbitrarily intertwined, JSC therefore needs a way to safely unwind the stack. JSC doesn’t have any knowledge about C++ stack frames - it just skips that part of the stack at once (no matter how many actual C++-function that actual are). For JS-function it is actual possible - and even required - to unwind function by function.

JSC stores the begin and end of the last active region of JS-stack-frames: VM::topCallFrame and VM::topEntryFrame.

Unwinding that region of the stack just follows the saved frame pointer on the stack until we reach topEntryFrame.

As soon as we have reached that frame, its predecessors are at least one or multiple C++ stack frames.

The problem now is that JSC doesn’t know how the compiler actually lays out the stack frame so we can only skip all C++ stack frames at once.

We already mentioned that calling into JS from native code requires to set up a VMEntryRecord.

That record stores (among other stuff) m_prevTopCallFrame and m_prevTopEntryFrame.

This allows us to skip all C++-functions at once by continuing unwinding from m_prevTopCallFrame.

We are now guaranteed to unwind JS-Functions again until we reach m_prevTopEntryFrame.

As soon as we reach it, we check the next VMEntryRecord for m_prevTopCallFrame and m_prevTopEntryFrame.

This process is repeated until m_prevTopCallFrame is null.

When calling into JS from C++, we therefore store the current VM::topCallFrame and VM::topEntryFrame in the VMEntryRecord as m_prevTopCallFrame and m_prevTopEntryFrame.

VM::topCallFrame and VM::topEntryFrame are initialized to the current call frame (of this intermediate function) and the actual callee’s call frame.

vmEntryToJavaScript/vmEntryToNative also need to restore the previous values when returning from the JS-Function.

When calling into native code we need to set VM::topCallFrame to the current call frame.

In C++ we start unwinding from VM::topCallFrame until we reach VM::topEntryFrame.

When we reach it, JSC checks VMEntryRecord whether there were JS stack frames before this point.

Short recap: The JS parts are unwound frame by frame, while the C++-parts are skipped all at once.

Unwinding starts at VM::topCallFrame.

Unwinding also needs to support inlined frames: DFG and FTL can inline a JS-function into another, however on the stack this is now one combined stack frame. Nevertheless unwinding should still be able to recover inlined functions. Otherwise stack traces would be missing some function calls.

Callee-saved registers Link to heading

Functions need to store and restore callee-saved registers it uses.

When unwinding the stack we might also need to inspect values in callee-saved registers, JSC therefore needs to be able to check where these registers where saved.

codeBlock is already passed when calling the function, codeBlock->calleeSaveRegisters() returns a list with the offsets of the stored registers on the stack.

LLInt, baseline JIT and DFG each have a fixed list of callee-saved registers they can use and always save and restore. Just FTL is able to save only those callee-saved-registers that are actually used by a function.

When we unwind the stack and need to check values in the callee-saved-registers, all callee-saved registers used by the VM need to be stored in the VMEntryRecord by copyCalleeSavesToVMEntryFrameCalleeSavesBuffer and later restored by restoreCalleeSavesFromVMEntryFrameCalleeSavesBuffer when calling into native code.

This isn’t done by default for normal native calls.

Saving all possibly used callee-saved-registers in the current VMEntryRecord seems to be needed for throwing exceptions and On-Stack-Replacement (OSR).

The other case where we would definitely need this is for determining GC roots - but since JSC uses a conservative GC the stack isn’t actually traversed but just examined word by word for references into the heap.

The main takeaway probably is that all callee-saved registers are only saved for certain actions (throwing exceptions and OSR), but not on each call from JS to native code. This makes it faster to call native functions. VMs with precise GC would probably need to store callee-saved registers each time they call into native code.

On 32-bit architectures some callee-saved registers are saved and restored when calling from C++ into JS by vmEntryToJavaScript and vmEntryToHost:

This is because JSC actually uses some callee-saved registers.

Although they are callee-saved registers, JSC uses them as caller-saved registers and therefore those registers only need to be saved when calling from native code into JS.

Having these thunks at the JS to C++-boundaries lets JSC use registers for different purposes than originally intended by the system’s ABI.

Conclusion Link to heading

Much of the information above is quite implementation-specific, nevertheless it is still very interesting how JSC manages to traverse the stack since quite a lot of functionality is affected by this (e.g. dumping stack traces, exception handling, etc.).